by Angelika Friedrich and Henry Whittlesey

Yesterday, we rang in the new year once again with the print publication of the transadapted stories serialized here online in 2021:

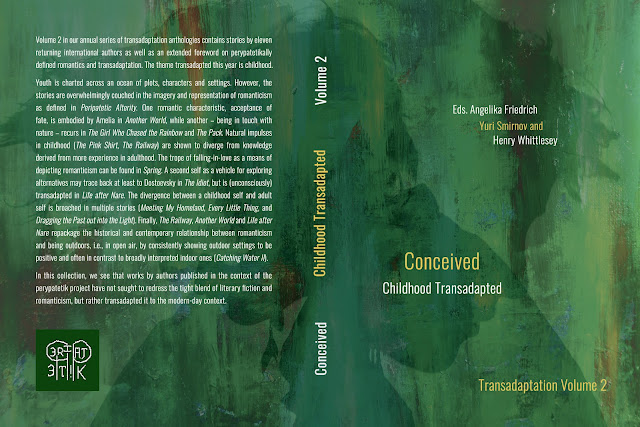

Conceived – Childhood Transadapted, (eds.) Angelika Friedrich, Yuri Smirnov and Henry Whittlesey (2021)

To improve your understanding of the perypatetik project, transadaptation and the relationship between the stories and perypatetikally defined romanticism (and pragmatism), we have also provided a lengthy foreword tying together a number of loose ends. Extracts of it are provided below, but the best grasp can be gained from the full introduction in the print and kindle editions, the expository work at perypatetik.net, in the treatise Peripatetic Alterity and the introductions to the transposition and transadaptation collections:

In the Middle – Prelude to a Contemporary Transadaptation, (eds.) Angelika Friedrich, Yuri Smirnov and Henry Whittlesey (2020)

Peripatetic Alterity: A Philosophical Treatise on the Spectrum of Being – Romantics and Pragmatists by Angelika Friedrich, Yuri Smirnov and Henry Whittlesey (2019)

From Wahnsinnig to the Loony Bin: German and Russian Stories Transposed to Modern-day America, (eds.) Angelika Friedrich, Yuri Smirnov and Henry Whittlesey (2013)

Volume 2 in our annual series of transadaptation anthologies contains stories by eleven returning international authors as well as an extended foreword on perypatetikally defined romantics and transadaptation.

The theme transadapted this year is childhood.

Youth is charted across an ocean of plots, characters and settings. However, the stories are overwhelmingly couched in the imagery and representation of romanticism as defined in Peripatetic Alterity.

One romantic characteristic, acceptance of fate, is embodied in Amelia from Another World by Jonay Quintero Hernández while another – being in touch with nature – recurs in The Girl Who Chased the Rainbow by Sarah-Leah Pimentel and The Pack by Alejandra Baccino. Natural impulses in childhood (The Pink Shirt by Talia Stotts and The Railway by Seyit Ali Dastan) are shown to diverge from knowledge derived from more experience in adulthood. The trope of falling-in-love as a means of depicting romanticism can be found in Spring by Marilin Guerrero Casas. A second self as a vehicle for exploring alternatives may trace back at least to Dostoevsky in The Idiot, but is (unconsciously) transadapted in Life after Nare by Nane Sevunts (Armine Asryan). The divergence between a childhood self and adult self is broached in multiple stories (Meeting My Homeland by Rayan Harake, Every Little Thing by Gennady Bondarenko, and Dragging the Past out into the Light by Kate Korneeva). Finally, The Railway, Another World and Life after Nare repackage the historical and contemporary relationship between romanticism and being outdoors, i.e., in open air, by consistently showing outdoor settings to be positive and often in contrast to broadly interpreted indoor ones (Catching Water II).

In this collection, we see that works by authors published in the context of the perypatetik project have not sought to redress the tight blend of literary fiction and romanticism, but rather transadapted it to the modern-day context.

Besides interpreting the works as further documentation of internationally and historically recurring aspects today, we can also analyze them against the backdrop of pragmatism and romanticism.

The characteristic of being metaphysical/spiritual makes up the core of romantics in Peripatetic Alterity, but a number of romantic characteristics feature especially prominently in childhood. The nubs of romanticism in childhood are (i) the spiritual/metaphysical (see chs. 3.1 and 6.2.1 of Peripatetic Alterity), (ii) accepting fate (ibid, chs. 3.2 and 6.2.2), (iii) life as a process (ibid, chs. 3.3 and 6.2.3), (iv) humor/laughter (ibid, chs. 3.8 and 6.2.8) and (v) love of freedom (chs. 3.12 and 6.2.12). They are the pieces that each child takes from the scaffolding around the building they are erecting and enjoys fiddling with in their construction until they disappear behind smooth facades and are often lost forever once the scaffolding is removed in adulthood.

Whereas the philosophical treatise adopts the approach of delineating the differences between pragmatists and romantics primarily on the basis of contemporary empirical findings, this collection shows the forms the metaphysical/spiritual takes in literary fiction, above all how childhood and youth are seamlessly interwoven with characteristics of romanticism.

Childhood and romanticism transadapted

The authors in the perypatetik project furnish a laundry list of transadaptations drawing on the themes of simplistic poetic romanticism and decay in materialism and consumption. In this volume Conceived, which is a collection of stories about childhood around the world, it is easy to see a contrast between the innocence of youth and worldly concerns of adulthood. In The Railway, for example, Seyit Ali Dastan recounts the innocuous story of a boy walking home from the hospital with his mother (who went for a pregnancy diagnosis). He slides down an iron guardrail again and again, races ahead of his mom on a tunnel-like path, climbs a bank, swings, disappears out of sight. This carefree youthfulness appears in direct contrast to his mother. She scolds him for falling from the guardrail, grabs his hand to keep him from running off, yells for him to come down from a bank, and so on. As a child, he is unaware of the risks and threats she knows from more experience. She is tied to the constraints imposed by the need to survive, bringing them to the attention of her son by correcting his natural risky impulses. Like the scene where Natasha Rostova spontaneously knows the dance steps in War and Peace, Ufuk, the boy, simply acts without consideration or knowledge of the consequences.

Acceptance of fate is another characteristic of romantics. Since children are largely forced to follow the dictates of their parents, they effectively exhibit this trait by nature, as Jonay Quintero Hernández depicts in Another World here. The story continues the plot of Amelia’s Euphemism from In the Middle. Evelio, the former(?) contract killer, Kunta (the cat he found), Luisa (a mother, Evelio’s neighbor) and Amelia (her daughter) moved from Madrid to El Hierro after Luisa murders her abusive husband and Evelio disposes of the body. Luisa knows none of this, essentially just waking up in El Hierro overnight and adopting the place as her home: “I felt quite disappointed and amazed about our sudden departure from Madrid … It feels kind of safe here with him.” Amelia’s judgment of the move does not extend beyond this. It is a fact. Fate.

Rather idiosyncratic coincidences between stories in Conceived and the characteristics of romantics can be seen in The Girl Who Chased the Rainbow and The Pack. One of the distinctions between romantics and pragmatists defined in Peripatetic Alterity is the former’s tendency to live in harmony with nature rather than chain themselves to obligations (chs. 2.12, 3.12 and 6.2.12). Living in harmony with nature is understood as “doing what comes naturally to each individual” (not something related to the environment, Henry David Thoreau, climate change, etc.). Although this characteristic is not associated with youth or childhood in Peripatetic Alterity, it is endemic to that phase of life. If you think of children in the playground, when they get bored of a game, they just stop without thinking about it. There is no analysis, no consideration of the other children’s feelings; they instantly end it. We see a brutal side of this in The Pack by Alejandra Baccino where three teenagers beat up a young homeless girl, the lead protagonist “Tina,” and steal her belongings. Similar to what we encounter in the other representations of childhood in this volume, the act is merely accepted as a fact and the protagonist continues (eventually even joining up with her attackers). An inspiring example of children’s acceptance of what is naturally present and thus their living in harmony with nature is told by Sarah-Leah Pimentel in The Girl Who Chased the Rainbow. This story is set in a multicultural Catholic school during the period of transition from Apartheid to democracy in South Africa (1990s). Since the Catholic schools there were private and did not have to abide by the segregated school policy during Apartheid, a diverse group of Black, Indian and White kids attended the one in Pimentel’s story. In the tense and fluid environment, race was obviously a topic of discussion in places like history class, especially just prior to the 1994 election of Nelson Mandela. When the narrator becomes an adult in the still fraught environment of the 21st century, she recalls the ease with which they had been able to have even explosive arguments and discussions during their school days because the pupils were accustomed to a multicultural environment and differences of opinion. Not mentioned, but implied is that the age, idealism and naturalness of childhood also contributed and accounts for the problem South African society has faced with this issue since then.

The natural innocence of children is also masterfully depicted in Talia Stott’s short story The Pink Shirt. A young boy goes shopping with his two sisters and mother. When he shows off his new salmon shirt to his dad, it is met with adamant disapproval because his father views the color as feminine and wants a masculine son. This prompts confusion and tears in the boy. When his mother (confusedly) tries to lay out her husband’s concerns, the boy replies, “I don’t like boys,” followed by the narrator revealing his interior monologue: “I didn’t like anyone. I had friends that were boys and some that were girls, but I hadn’t like liked anyone yet.” He just wants to play games and watch TV, as he explains later. His carefree childhood is not preoccupied with sexuality, its implications, the family politics surrounding it. His nature tells him that he likes a salmon shirt, and it is fashionable. End of story. In contrast to this natural impulse, especially his father interprets something. He judges, analyzing his son against an ideal he has in his head.

Modern-day love

“And then there’s me, I’m the kind of girl who thinks ‘the greatest gift in life is to love and be loved in return’, a frase famose I can’t forget from the filme Moulin Rouge,” (92) says the first-person narrator in A Girl Pedaling by Marilin Guerrero Casas. She expands on this theme, by which she means “falling-in-love,” in Spring, recounting her own amorous adventures as well as those of her friends. She describes falling-in-love in passionate language tied to expectation/hope, associating it unambiguously with the season of spring: “Winters can be hard. Some of us think of them as the worst season of all but they are so much more bearable when you are looking forward to spring. So, keep holding on. Life is so much better when you don’t easily give up, when you fight strongly for what you believe in. And I believe in hope.”

Consistent with one of the defining traits of metaphysical romantics, falling-in-love for Casas is destiny, something totally out of her control and to which she willingly submits. When she meets her new boyfriend, it is initially something intended to be a relaxed, fun friendship with benefits: “I wasn’t sorprendida when he told me he was an arquitecto. Certainly he was. The way he dressed and his ‘I do what I feel like’ estilo revealed too much of him. The atracción was immediate. It was tiempo de relajación and fun with a bit of romance, of course. That was just me. We spent great nights together drinking wine, listening to Ed Sheeran songs and having mind-blowing sexo.” Without any interruption in the plot, the first-person narrator moves immediately to the possibility that this relationship is destined to be more than she anticipated. Rather than resist, rather than try to guide it, she readily acquiesces:

“And suddenly I was involved in another relación when I hadn’t even asked for it. Life can be very impredecible sometimes. When you don’t want things heading in one dirección, somehow they mágicamente wind up the way you didn’t expect it. And I couldn’t help but wonder, do we always need to take control of our lives or is it sometimes better to follow the path that some fuerza sobrenatural has designed for us? Well, if you believe in destino… then you have your answer.”

This acquiescence to fate intensifies the romantic orientation of the protagonist Pat. Accepting fate is one of the core characteristics of a romantic (as opposed to pragmatists who determine their fate – see chs. 3.2 and 6.2.2 in Peripatetic Alterity). Pat’s rhetorical questions here are implicitly answered by the suggestion that she believes in destiny (destino). These characteristics are also in harmony with her acceptance of processes, another core trait of romantics (see chs. 3.3 and 6.2.3 of Peripatetic Alterity), as we saw above in Pat’s attitude toward the seasons (“Winters can be hard… [they are] more bearable when you are looking forward to spring”]. Casas’s deep-seated belief in the process of life is explicitly announced at the beginning of A Girl Pedaling: “Life is a roller coaster. There are rises, falls, twists and turns we cannot always anticipar. (In the Middle, 89).

Casas also sees a downward trajectory from the period of falling-in-love, not unlike what we witness with Avdotya in The Harvest. Whereas the narrator suggests this in Avdotya’s move from outdoors to indoors, Casas shows the departure from this divine phase in the protagonist’s decision to live together with her boyfriend (or attempt it): In the first case, which unfolds in A Girl Pedaling and is revisited briefly in Spring, the partner turns out to be an “absolute asshole”; and in the latter story, the first-person narrator is hesitant when her boyfriend suggests it.

This theme of deterioration in love also crops up in Till Love Do Us Part. Alejandra Baccino charts out the full cycle of a relationship from falling-in-love to discovering betrayal. The protagonist falls in love with an intense, dominating guy. Naturally, she is very happy in the early days and enjoys the type of bliss common during the falling-in-love phase. Yet, as the relationship deteriorates, he becomes physically violent, mentally abusive and ultimately cheats on her, she adamantly defends him because he still brings her such pleasure at times. In other words, she is able to depart from the banality of worldly matters through this relationship. Presumably, this is the only avenue she has to achieve these metaphysical moments, so she is very reluctant to abandon him. After the early phase (falling-in-love), the parts not relating to abuse and violence are teeming with physical objects as a representation of alleged love. Baccino shifts from telling about intense eyes, staring, passion and emotion during the falling-in-love phase to classic cars, a white suit, a bouquet of flowers afterwards. And, not surprisingly, the next stage after this material turn is for her to find him in bed with another woman.

Two selves today

In the first volume of these transadaptations, In the Middle, Nane Sevunts (Armine Asyran) shows how the socially constructed self is sometimes posited in sharp contrast to an alternative identity that enjoys unlimited freedom (воля). In Unreal Reality, we see Julie gain access to this second self in Nare. Fear, special treatment, loneliness and depression are what she has felt since the moment her toy teddy bear emitted a ‘booo’: “Fear. The first emotion she experienced from interaction with the world was fear. She simply assumed that the world was not a safe place.” (In the Middle, 1) Eventually, after leaving her family and travelling aimlessly, she lands in a mental hospital. In the subsequent course of events, we realize that Julie’s collapse was brought about by her incompatibility with the limitations in material life. The language completely changes between the phases when Julie escapes with Nare (i.e. free) and when she is alone without her (i.e. constrained): The language in society is couched in negativity: “suffering,” “overcoming emotional barriers,” “shrinking,” “violent face,” “brutal treatment,” “demons,” “hell,” “depression,” and “pills”; when released from the constraints, it is infused with the buoyancy of “unlimited possibilities,” “light,” “songs of the birds,” “nourishment,” “happiest,” “laughing and running.” The words laughter and happiness are repeated in many different contexts shared by Julie and Nare. Without directly declaring that her unhappy state is brought about by the materialism of her surroundings, Julie clearly depicts the flights into her alternative self as metaphysical:

From time to time, Julie would leave Nare and return to the real world. She was bored and unhappy in this world, but these moments happened. Most of the time she was in the real world. The world offered nothing to her but wanted her attention and care and love. The world gave nothing to her but wanted every single element of her. And she was exhausted in this world. (6)

The second self is effectively identified as metaphysical while the first self is material. The narrator blurs the boundary between Julie and Nare, leaving it unclear whether they are the same person or whether Nare is a special friend who gives Julie access to her alternative self. Either which way, Julie with/as Nare is liberated from social constraints, while Julie without Nare is restrained by them. The deixis of “this world,” “real world” vs. “that world” emphasizes the duality. Furthermore, as mentioned above, the language changes between them. The value judgements on each are also unambiguous: The metaphysical one consists of “precious moments,” while the material one is “full of hatred and humiliation.”

In this volume, the authors repeatedly show the strengths and weaknesses of romanticism in childhood. A child’s lack of experience means that they must rely on their parents for “knowledge.” This age-imposed naivety can result in a distorted picture. In Meeting my Homeland, Rayan Harake describes a child’s assumption of normality in her earliest days similar to the other authors. Likewise, the abnormal aspects of this upbringing are only realized retrospectively as an adult. While the protagonist has some idea that her father’s domineering nature, his mockery of emotions, and strict censorship of television are excessive, she has no idea, for example, that headaches exist, in part because she doesn’t suffer from them and in part because her father adamantly denies their existence. That is the natural world she grew up in, at best only partially questioned.

Childhood also assumes romantic characteristics in Gennady Bondarenko’s story Every Little Thing. Its mixture of fun, inspiration and humor is viewed in contrast to adulthood, with the dividing line between the two phases being marked by the end of high school, specifically a motorcycle crash. In the story mostly about Klaus and Igor during their last year of high school, the teenagers relate funny stories from the past or goof around: Klaus is supposed to play the Russian Father Frost, Ded Moroz, but turns up as Santa Claus with a cotton beard, hence his name; in class, they sing a Beatles song to introduce their city of Odessa (and the teacher catches them, but gives them the best grade anyway); in another anecdote, the boys have written to the Beatles Fan Club in England and received a response from it, which they open to much amusement at their new English teacher’s apartment.

This youthful phase of fun and games ends after graduation: “the beginning of adulthood caught us unexpectedly,” says Igor. Now the language turns into “smiling mysteriously into his beard,” “no regrets,” and moral judgements such as “it is plain weird when you don’t know your native language.” In the fall vacation, the end of youth is depicted in even clearer terms when the former band member Klaus can no longer sing and play (“No way! Out of practice”), but then performs an acoustic song prompting Igor to despair: “it only took you a few months after school to become such a…”

This shift from humor or fun for the sake of fun in youth to morality in adulthood mirrors a classic distinction between romantics and pragmatists (see chs. 2.8, 3.8 and 6.2.8 in Peripatetic Alterity). Bondarenko does not necessarily see humor as absent from adulthood, as he has shown in House with a Stucco Ship. Here, however, youth is associated with humor and, similar to Turgenev, cultural fantasy through Santa Claus and contemporary fantasy through the Beatles and thus the implied dream of becoming rock stars.

Another contrast between the innocent acceptance of youth and critical judgement in adulthood unfolds in Dragging the Past out into the Light by Kate Korneeva. In reflecting on the cause of her current issues, the narrator realizes that the unconscious suppression of her femininity in childhood had a detrimental impact. In other words, because her mother had a preference for boys, the narrator instinctively acquired masculine characteristics to feel the parental love she craved. Yet she wanted emotion (a “mom’s emotional embrace, wealth, intimacy”), which her mother refused to give. This causes her pain to the present day, when she, as an adult and thus no longer accepting fate unquestioningly, wants to change her: “My pain is not only about not having a mother with her acceptance and unconditional love. It is also about being unable to change her now.” The adult narrator no longer accepts fate. She has broken with this core characteristic of romanticism, having evidently converted to pragmatism, the shaping of people and the determining of the future (see chs. 2.2 and 6.2.2 of Peripatetic Alterity).

Transadapting freedom

Enclosed places often bear negative connotations of confinement and dissatisfaction, while the reverse holds true in open areas. These settings mirror another side of the nature theme looked at earlier in the context of youth and discussed at length in Peripatetic Alterity. Many stories in the anthologies In the Middle and Conceived suggest that the authors share similar views. While certainly not universal, the authors frequently set negative plot developments either indoors or in cities. Furthermore, characters that are more problematic or have more issues are found in urban contexts. By contrast, freedom is implied by plots unfolding in natural environments or at least outdoors.

In The Railway by Seyit Ali Dastan, the two characters leave a hospital, where the mother had pregnancy tests, and walk home through rural farmland on the outskirts of the city. The seemingly innocuous story about an energetic Turkish boy constantly escaping from his attentive mother becomes particularly interesting when viewed against two urban stories by Javier Gomez, also in the collections: Catching Water I and II. Here, the protagonist Nadia is in an abusive relationship with her boyfriend. The Turkish boy may slightly hurt himself, get a little lost, disregard his mother, but these developments are harmless and coupled with moments of exquisite beauty, such as when he sees his mother standing with her headscarf removed, her coat blowing in the wind, not moving at all. By contrast, Nadia, in the midst of an Argentinian city, working in a bookstore, living in an apartment, constantly faces the threat of her boyfriend’s aggression. In one instance, he beats her badly; in another, even the park cannot help them, as they start yelling and then physically fighting.

The constituent elements of their lives reflect the existential innocence of the boy and the material desolation of the girl. Dastan’s story is teeming with grass, brush, spring rain, cabbage, silverberry trees, irrigation channels, a creek, pebbles, poplar trees, while Nadia’s profanity-laced environment, beginning with a plant she sends “on a suicide mission towards the floor,” consists of rock bands, headphones, smoke, hangovers, weed, beer, etc. It should come as no surprise that the stories wrap up on completely different notes: The boy and his mother continue their walk home together, with the narrator joking about unrealistic promises the boy made, but failed to keep; Nadia, by contrast, has a “black eye and a shattered crystal heart” without any likelihood of being able to reset her life.

This divergence between urban (indoor) and rural (outdoor) life is illustrated spectacularly in Jonay Quintero Hernández’s two (serialized) stories Amelia’s Euphemism and Another World. The former is set in Madrid, the latter in El Hierro. Amelia’s Euphemism begins with the lead protagonist, Edelmiro, a professional assassin, blowing the brains out of a man near the slums of Madrid. It continues in chapter two with a gipsy clan that controls the narcotics market in the south of the city, where the leader neglected and abused a cat subsequently named Kunta, nearly killing him before Edelmiro finds and rescues him. The cycle of violence does not end there. In later chapters we learn about Edelmiro’s neighbor, Luisa, who is regularly abused by her husband. One night she fights back with one of his trophies, and Edelmiro disposes of the body for her. This series of events in the urban environment is nearly completely in contrast to Edelmiro’s and Luisa’s life in the rural setting of El Hierro, where they move after the murder. Another World may begin with a foggy sky, chilly air, but this weather along with squawks, moos, and neighs is a far cry from the contract murder to start Amelia’s Euphemism. On El Hierro, animals are thriving; kids are “taller, stronger,” and practice “a lot of outdoor sports like soccer, swimming, mountain biking, fishing, etc.” One teenager is building a house with his father. The idyllic backdrop climaxes with Edelmiro and Luisa dancing at un baile in the village’s main square.

These scenes during the day in Another World capture a range of harmonious environments from the island as a whole with beauty and nature and festivals to the improvised family life, kids at school and “related” neighbors. Daytime, however, appears to be factor as well. There is a recurring difference between being outside during the day and at night. The former is almost universally associated with positive plot twists or scenes in the stories of both In the Middle and Conceived. As we just described, all of Hernandez’s outdoor, daytime scenes can be characterized as such, but not necessarily night-time ones: In both Amelia’s Euphemism and Another World, a person is shot outdoors at night. We see a similar ambiguity with night-time scenes in Catching Water II. Nadia is often in the city parks without her boyfriend, many of which are perfectly pleasant fun and certainly without violence or conflict – during the day. It’s a different story at night: To start Catching Water II, Gomez describes Nadia on her rooftop at night, brooding over “something [that is] off”; at a party later, again in the dark of evening, she is dragged inside by her boyfriend who then assaults her. Finally, a walk in the lamp-lit park shifts from pleasant silence to a physical fight when Ale confronts her about kissing another guy (in the past).

An outdoor setting is also frequently the stage for regeneration and humor. In Life after Nare, Julie receives critical advice in a park, an experience that sparks her regeneration. The two funniest scenes in Meeting my Homeland occur outside: one being when the protagonist puts on her hijab the wrong way and goes outdoors; the other being when she forgets it and only realizes this in front of her building as she sees her cousin approaching. Presumably, the author, similar to Bondarenko, has related these humorous anecdotes because they suit the story, but, by integrating laughter for the sake of laughter (not a moral agenda), she, he or they have tapped into one of the defining traits of romantics.

Conclusion

While all these depictions share certain commonalities, in particular the broaching of the romantic orientation as a poetic alternative even in the event of worldly failure, the authors’ immediate treatment of each topic is complemented by an even more far-reaching, extensive and nearly universal aspect of the metaphysical: the shifting between different worlds, diverging states, the cyclicality of being when a worldly person consciously or unconsciously embraces romanticism. In part, this is an inevitable consequence of a metaphysical orientation. As Julie says in Unreal Reality, it is necessary to return to the real world from time to time. It is not possible, and for many not even desirable, to remain in one state, whether positive or negative, for an interminable amount of time. Romantics live for this diversity, as is revealed time and again in literary fiction and our everyday lives. What we need to fathom it, is very simple, just one thing: air.

There is both literal and metaphorical significance to the term air.

On the one hand, it is physically required for achieving the necessary balance to reject materialism and embrace the metaphysical, as we have discussed in Peripatetic Alterity and can see explicitly in Life after Nare by Armine Asryan. When Julie is having difficulty in the confines of society again, she goes to a park (i.e. again outdoors) and consults an elderly man with “the first miracle smile she had ever seen.” His ideas help Julie restore balance, with the second one being “to work with your breath”: “Julie started working with her breath before the candle. Every day. She was persistent. She wanted to save herself. She lost a couple of pounds after the breathing exercises. That was funny because she never thought she would lose weight from the breathing exercises. She felt stronger and stronger.” In the fresh air of the park, she learns about deep breathing that in turn liberate her from being the allegorical mosquito that is sucking the blood of other people around her to survive, i.e. ‘consuming’: “She wished she could fall down one day like a little mosquito and die. But that would be too easy for someone that had a long way to go. She did not die and she continued sucking the blood of the others.” Yet now Julie needs nothing but air to survive.

On the other hand, air acts as a symbol for the presence of the metaphysical at given moments. It is certainly possible that this practice derives from Christianity (e.g., air is often associated with the Holy Spirit) and that Christianity drew on pagan or other traditions that adopt air, wind, the ether, etc. for the spiritual. In episodes of metaphysical exposure discussed elsewhere, the word air or wind either appears, is implied or can be assumed in almost every context. For example, in Elias Portolu, Zia Annedda indirectly refers to the idea of air by tapping her breast and referring to a bird flying (in the air). In Anna Karenina, Levin’s realization comes as thunder clouds are gathering and it begins to rain – almost certainly accompanied by wind. The evidence of the domovoy in Byezhin Prairie is proven by gusts of wind opening doors. There is a direct reference to wind in The DNA of Angels, when the narrator describes Masha’s final vision of her late husband: “The wind swept over the field…” Flags rippling (in the wind), her soul soaring (through the air), are part of the description in the trope of Avdotya’s falling-in-love in The Harvest. By the same token, the concept of air is also implied throughout Unreal Reality, with the metaphysical scenes set outdoors under the open sky (rather than indoors), and in Life after Nare, with the park scene and the allegorical story of the rabbit that is unhappy at home and goes outside for freedom. Finally, when Ufuk sees his mother standing with her coat blowing in the wind, arms extended, in The Railway, she is visualizing the girl in her womb.

Series

January: The Pack – Alejandra Baccino (Uruguay)

February: The Pink Shirt – Talia Stotts (America)

March: Dragging the Past out into the Light – Kate Korneeva (Russia)

April: Looking Forward to Spring – Marilin Guerrero Casas (Cuba)

May: Every Little Thing – Gennady Bondarenko (Ukraine)

June: The Girl Who Chased the Rainbow – Toni Wallis (Sarah-Leah Pimentel) (South Africa)

July: Another World – Jonay Quintero Hernandez (Spain)

August: Life after Nare – Nane Sevunts (Armine Asryan) (Armenia)

September: Meeting My Homeland – Rayan Harake (Lebanon)

October: Catching Water (Part Two) – Javier Gomez (Argentina)

November: Remember – Seyit Ali Dastan (Turkey)

December: Exposition: Conveyors of the Metaphysical in Literary Fiction – Cases Studies from In the Middle, Conceived and Literary Fiction

Background – Context

In the Middle – Prelude to a Contemporary Transadaptation, (eds.) Angelika Friedrich, Yuri Smirnov and Henry Whittlesey (2020)

Peripatetic Alterity: A Philosophical Treatise on the Spectrum of Being – Romantics and Pragmatists by Angelika Friedrich, Yuri Smirnov and Henry Whittlesey (2019)

La Syncrétion of Polarization and Extremes Transposée, (eds.) Angelika Friedrich, Yuri Smirnov and Henry Whittlesey (2019)

The Codex of Uncertainty Transposed, (eds.) Angelika Friedrich, Yuri Smirnov and Henry Whittlesey (2018)

L’anthologie of Global Instability Transpuesta, (eds.) Angelika Friedrich, Yuri Smirnov and Henry Whittlesey (2017)

From Wahnsinnig to the Loony Bin: German and Russian Stories Transposed to Modern-day America, (eds.) Angelika Friedrich, Yuri Smirnov and Henry Whittlesey (2013)

Emblems and stories on the international community

Perception by country – Transposing emblems, articles, short stories and reports from around the world

Credits

Cover photo: Eskişehir, Turkey – Schizophrenia – Phovius (Unsplash) + Yellow – Sergeon (Unsplash)

Source: The Codex of Uncertainty Transposed